Glimpses of the ultrafast world of electrons are altering scientists’ imaginative and prescient of the internal workings of atoms and molecules. The 2023 Nobel Prize in physics goes to 3 physicists who illuminated this realm with ultrashort pulses of sunshine, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences introduced October 3.

Physicists Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier will cut up the 11 million Swedish kronor (about $1 million) prize, awarded “for experimental strategies that generate attosecond pulses of sunshine for the research of electron dynamics in matter.”

Ohio State College; © MPI for Quantum Optics; boberger/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Inside atoms and molecules, electrons zip round at excessive speeds. Capturing their to-and-fro is feasible solely with pulses of sunshine which are extraordinarily brief. It’s akin to a digicam flash that lasts mere attoseconds, or billionths of a billionth of a second.

People have lengthy strived to measure processes with rising precision, says Peter Armitage, a physicist at Johns Hopkins College. “With the arrival of lasers, the timescales that you would measure grew to become shorter and shorter [because] you’re doing it with ultrafast gentle pulses.”

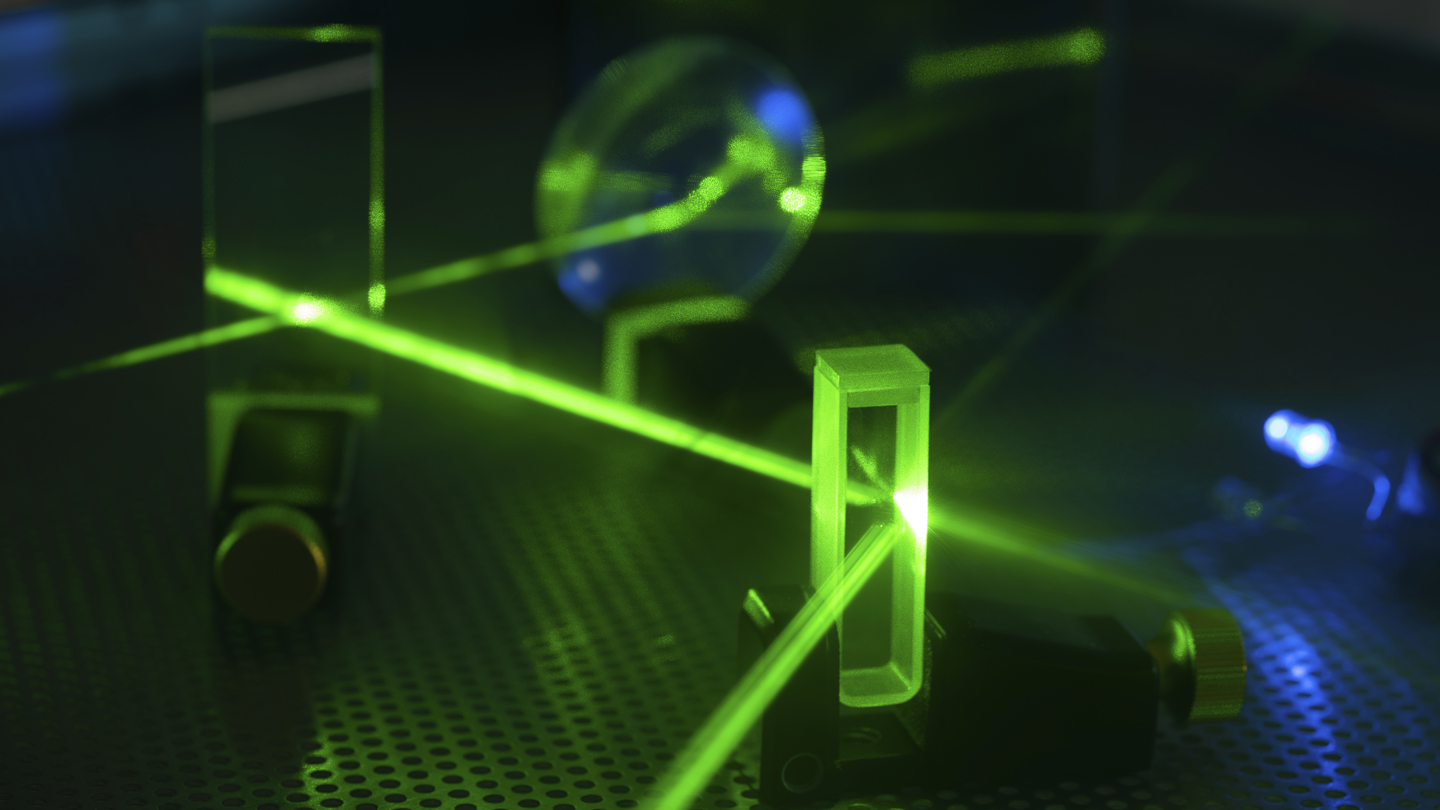

Over many years, researchers have honed the power to create such near-instantaneous bursts of sunshine (SN: 3/12/10). Within the Nineteen Eighties, L’Huillier, now at Lund College in Sweden, observed that infrared laser gentle despatched by a fuel would create gentle of a wide range of wavelengths, what’s often known as high-harmonic technology. The impact is a results of how that gentle interacts with the electrons within the fuel, by a course of which L’Huillier’s analysis helped make clear.

These different wavelengths, often known as overtones or harmonics, are just like the overtones that assist give musical devices their distinctive sounds. Including collectively the precise combos of overtones ends in very brief pulses of sunshine. With this methodology, researchers led by Agostini, now at Ohio State College in Columbus, in 2001 produced a sequence of sunshine pulses, every of which lasted simply 250 attoseconds. The identical yr, Krausz, now on the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching, Germany, and colleagues created single pulses lasting simply 650 attoseconds. At present, scientists could make a lot shorter pulses tens of attoseconds lengthy.

“I used to be personally fascinated by this discipline from the beginning, and because of this I continued with it throughout many, a few years,” L’Huillier stated in a cellphone name in the course of the announcement. L’Huillier is just the fifth girl to obtain the physics Nobel. “There usually are not so many ladies that get this prize, so it’s very, very particular,” she stated.

Scientists have used this method to discover the conduct of electrons inside atoms and molecules. For instance, the approach has revealed the timescale for the photoelectric impact, wherein gentle knocks an electron out of an atom, and particulars of quantum tunneling, wherein electrons move by obstacles that appear insurmountable (SN: 7/6/17).

The approach additionally reveals the conduct of molecules. “You possibly can watch the motions of molecules themselves, primarily to make motion pictures of molecular movement,” Armitage says. “And that is of huge curiosity for all types of issues: for [everything from] understanding why some supplies are superconductors at excessive temperatures to photovoltaic functions, harvesting vitality from gentle…. I feel it’s actually excellent at first.”

Robert Rosner, a theoretical physicist on the College of Chicago, says one software includes designing supplies from scratch.“Chemistry is all about how electrons … work together with each other,” he says. “It’s like constructing a home, and that you must know what goes first and what’s the subsequent step.” However on this case, you wish to comply with what the electrons do throughout chemical synthesis — which is one thing ultrashort gentle pulses can do. “It actually opens up a completely new mind-set about how we really make stuff.”