After discussing the points regarding Leh’s groundwater in Half 1, it’s time to focus on a few of the actionable options obtainable for the native administration, companies, and residents. Addressing the gargantuan extraction of Leh’s groundwater and enhancing its high quality would require a mixture of recent options and leveraging conventional programs of water administration.

Beginning out, Dr Lobzang Chorol — who earlier this yr accomplished her PhD from IIT-ISM, Dhanbad, after finding out Leh’s groundwater programs for over six years — advocates for stricter regulation of groundwater extraction. Whereas a few of the measures she has listed beneath are already being carried out to some extent because of the Union Authorities-sponsored Jal Jeevan Mission, extra must be achieved on conflict footing to make sure long-term outcomes.

1. Necessary permits: All people, companies, and establishments must be required to acquire permits for drilling borewells and extracting groundwater. Permits must be granted primarily based on a radical evaluation of the native groundwater sources and the sustainability of extraction. Authorities, together with the Public Well being and Engineering Division, should mandate a radical website inspection earlier than granting permissions for the development of latest borewells or septic tanks.

2. Metering of groundwater utilization: The set up of water meters must be made obligatory for all groundwater extraction factors. This may assist monitor and regulate groundwater utilization, guaranteeing that extraction stays inside sustainable limits.

3. Pricing of groundwater: Introduce a pricing mechanism for groundwater utilization to discourage extreme extraction and promote conservation. This may be within the type of a groundwater tax or a tiered pricing system primarily based on consumption ranges.

4. Zoning laws: Implement strict zoning laws to regulate the density of borewells and forestall over-extraction in essential groundwater recharge areas. This may occasionally contain establishing ‘no-go’ zones the place groundwater extraction is prohibited or restricted.

5. Strict enforcement of waste disposal laws: Implement stringent laws on the disposal of stable waste, sewage, and industrial effluents to stop contamination of groundwater. This could embrace obligatory remedy of waste earlier than disposal, common monitoring of disposal websites, and hefty fines for inns and different companies discovered dumping waste — together with expired cement into water our bodies. Furthermore, clear tips should be set on the minimal distance that should be maintained between borewells and septic tanks, primarily based on the native hydrogeological situations and the potential danger of contamination.

6. Launch a public consciousness marketing campaign: To coach residents in regards to the significance of sustaining the right distance between borewells and septic tanks, and the potential well being dangers related to groundwater contamination.

7. Set up water-efficient fixtures: Encourage inns, guesthouses, and eating places to put in water-efficient fixtures, equivalent to low-flow taps, promote use of greywater recycling programs, and use handled water for non-potable functions like irrigation and bathroom flushing. They need to even be mandated to endure common water audits, set up rainwater harvesting programs, and obtain monetary incentives like tax cuts in the event that they meet sure water conservation targets.

“To persuade the trade to speculate urgently, we have to emphasise each the environmental necessity and the potential for value financial savings by way of environment friendly water use. Collaborating with eco-tourism certification programmes might present a further incentive,” she provides.

8. Common monitoring and mapping of groundwater sources: Set up a complete groundwater monitoring community and frequently map the groundwater sources to evaluate the impression of extraction and inform regulatory selections. It is a significantly necessary concern given the dearth of concrete knowledge on the dimensions of groundwater extraction in Leh.

Chatting with The Higher India, Dr Farooq Ahmed Dar — assistant professor on the Division of Geography and Catastrophe Administration, College of Kashmir — agrees with this suggestion.

“Lengthy-term monitoring programmes, measuring the traits in groundwater ranges, figuring out potential dangers, and evaluating the effectiveness of conservation measures carried out in Ladakh now and again are essential steps that have to be taken,” he notes.

On the dearth of concrete knowledge, Dr Dar notes, “The foremost concern concerning the groundwater and its relationship with totally different environmental elements is the dearth of the information and understanding of its hydrodynamic processes. Understanding the programs, significantly the underground aquifers, is necessary. There’s a essential want to amass knowledge and collect correct and dependable data on groundwater amount, high quality, and move dynamics.”

“Trendy instruments and strategies like distant sensing, geophysics, tracers, and so forth are broadly used to deal with groundwater issues. For this funding of analysis and growth (R&D) tasks is important. The consequences of anthropogenic actions, equivalent to inhabitants development, urbanisation, and land use modifications on groundwater sources have to be quantified. Integrating superior modelling strategies will help on this route,” he provides.

Radically enhancing Leh’s sewage remedy system

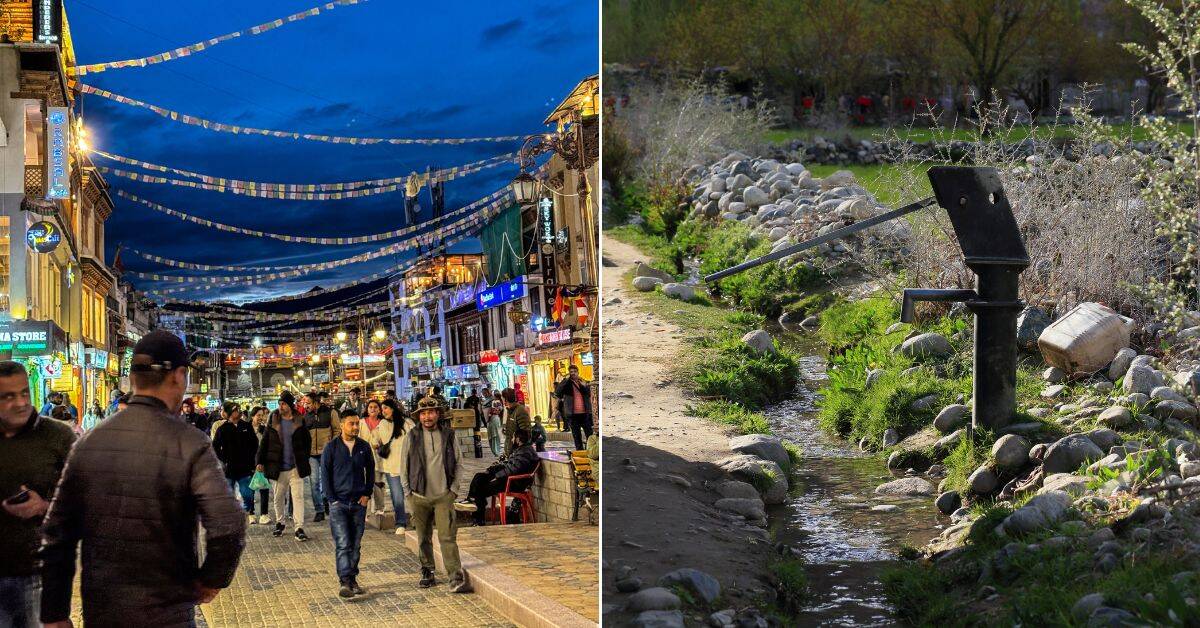

Concerning Leh’s wastewater remedy amenities, the present state is insufficient to fulfill the rising calls for of the inhabitants and to make sure the protection of ingesting water.

As Dr Chorol notes, “The present amenities are ageing and lack the capability to deal with the growing quantity of wastewater generated within the metropolis. Important investments are required to improve and develop the water remedy infrastructure in Leh.”

Considered one of these steps embrace upgrading the prevailing Sewage Remedy Crops (STPs) and establishing new ones in areas presently not coated by the sewage community. Authorities should additionally put money into superior water remedy applied sciences, equivalent to membrane filtration, to make sure handled water meets prescribed requirements for protected consumption and environmental discharge.

“We additionally have to develop the sewage assortment community to cowl all households and institutions in Leh. Additionally, we have to set up an everyday water high quality monitoring programme to make sure that the handled water meets the prescribed requirements and to promptly determine any potential contamination points,” she says.

The precise funding required to take all these measures will rely on an in depth evaluation of the present infrastructure and the projected future wants.

Extra importantly, nevertheless, Leh wants a decentralised sewage remedy plan. Whereas a centralised sewage remedy plant can be very best, it could certainly face vital obstacles given Leh’s mountainous terrain and scattered settlement sample.

Chatting with The Higher India, Dr Chorol says, “After additional consideration, I imagine a decentralised strategy could be extra appropriate and sensible for Leh.”

Based on her, this contains:

1. Small-scale remedy programs: We might implement a number of smaller remedy amenities strategically situated all through Leh. These might serve clusters of households or neighbourhoods, lowering the necessity for in depth piping throughout troublesome terrain.

2. Superior septic programs: Selling using trendy, environmentally-friendly septic programs for particular person households or small teams of properties might be efficient. These programs can deal with wastewater to a better commonplace than conventional septic tanks.

3. Constructed wetlands: The place house permits, we might create synthetic wetlands designed to naturally filter and deal with wastewater. This eco-friendly strategy might work nicely in some areas.

4. Dry bogs and composting programs: Given Leh’s water shortage, increasing using waterless bathroom programs might considerably cut back the amount of sewage produced. Whereas establishing these bogs in the principle city will likely be troublesome given sure logistical constraints, inns, visitor homes, and homestays in villages ought to do extra to encourage their use.

Implementation of those steps requires detailed mapping of Leh’s settlements and topography, severe and constant group engagement, and collaboration with environmental engineers skilled in high-altitude and cold-climate sanitation. There must be a phased roll-out of every of those steps with pilot tasks in key areas.

“This decentralised strategy can be extra adaptable to Leh’s distinctive geography and might be carried out extra rapidly and cost-effectively than a centralised system. It could even be extra resilient, as an issue in a single small system wouldn’t have an effect on your entire space’s sanitation,” Dr Chorol says.

These steps are essential given how groundwater is primarily utilized by households, industries, inns, and numerous establishments, significantly within the Leh city space.

Chatting with Mongabay, Dr Farooq Dar said, “No matter water is pumped from the underground reserves, roughly 93% of that’s used for these functions. Ladakh can also be shifting in the direction of self-sufficiency within the meals and crop market.”

“This additionally calls for large [amounts of] water, and for that, folks drill wells. The remainder of the pumped groundwater is sort of 7%, utilized in crop fields, greenhouse vegetation cropping, fruits, and different crops not earlier grown within the area. Groundwater can also be pumped by the resort and guesthouse house owners as they require contemporary water for the vacationers around the yr,” he added.

Leveraging native information

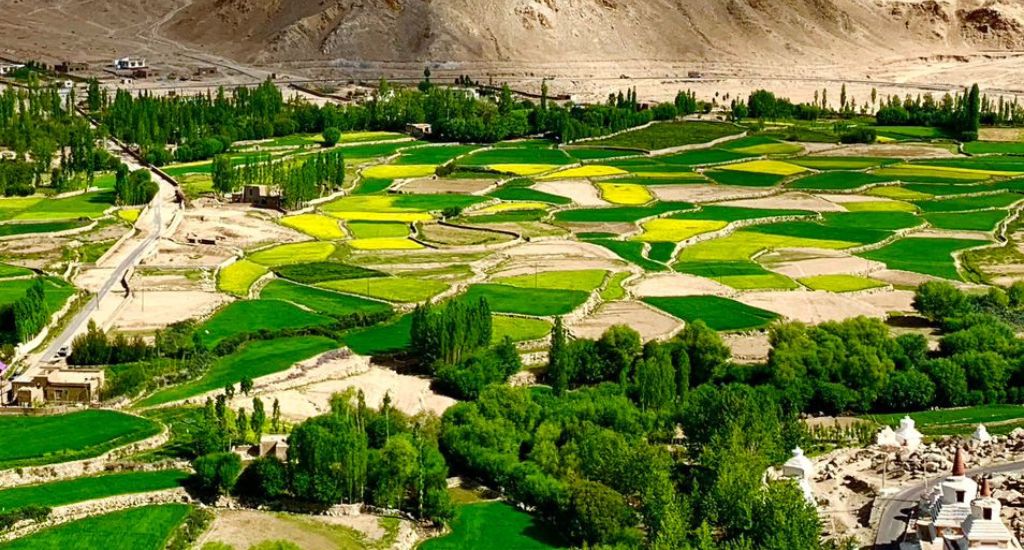

Given the rising dependence on groundwater in native agriculture for rising water-intensive crops, it’s essential to hark again to conventional programs of water administration.

As Dr Chorol notes, “The folks of Ladakh have developed an extremely refined conventional ecological information over generations of residing on this harsh, high-altitude atmosphere. Their intimate understanding of native hydrology, revolutionary irrigation strategies, and resource-efficient architectural designs are really outstanding.”

“To elaborate on leveraging native information programs for sustainable water use practices, we will draw priceless insights from conventional water administration programs like these present in Ladakh. As an illustration, the Ladakhi system of appointing a chhur-pon or ‘water lord’ chosen by villagers demonstrates how native communities can successfully govern their water sources. This mannequin might be tailored to empower native water committees in different areas.”

However how does water historically move in rural habitations?

In a 2006 paper titled ‘Conventional irrigation and water distribution system in Ladakh’ for Indian Journal of Conventional Information, authors Dorjey Angchuk and Premlata Singh clarify, “The melted snow water from numerous rivulets, known as kangs-chhu (ice water) merging sooner or later varieties a togpo (stream) that flows by way of a valley touching many villages related by the channel, known as ma-yur (mom channel). It’s constructed alongside a mountainside that varieties its retaining wall, and is lined with clay to carry the water. That is termed the Ladakhi model of a dyke.”

“At some locations rocks are damaged to permit the passage of water or else the place the rocks are too laborious, a hole poplar or willow trunk, known as va-to is reduce into two equal halves to permit the water straightforward passage. Water from the ma-yur is additional diverted into yu-ra (small canals), which irrigates the fields. The purpose from the place togpo water is diverted into ma-yur, and ma-yur water into yu-ra is known as yurgo; and ska is the purpose from the place yu-ra water is diverted to the sector. Water within the ska is additional guided by way of channels referred to as snang, which carry the water into the sector.”

In the meantime, the rotational water distribution system (bandabas) in Ladakh ensures truthful allocation and might be studied and formalised in different areas to advertise equitable water sharing.

How does it work? Based on Dr Chorol, “The bandabas system is a conventional methodology of water allocation that has been practised in Ladakh for hundreds of years.”

Right here’s the way it works on the bottom:

- Villages are divided into sections, every with a chosen water supervisor known as a chhur-pon.

- Water from glacial streams is directed right into a community of canals.

- Every part of the village is allotted water for irrigation on a rotational foundation, sometimes for a set variety of hours or days.

- The chhur-pon is accountable for opening and shutting the water channels to make sure truthful distribution.

- This rotation is often decided by the dimensions of land holdings, with bigger farms receiving proportionally extra water time.

- The system is versatile and could be adjusted primarily based on seasonal water availability and crop wants.

- Group conferences are held to debate and resolve any disputes or modifications wanted within the water allocation.

“Indigenous engineering strategies, equivalent to Ladakh’s intricate canal programs (ma-yur, yu-ra), showcase native ingenuity in adapting to difficult terrains. By finding out and making use of such native engineering information, we will develop context-appropriate irrigation options elsewhere,” explains Dr Chorol.

However how do these intricate canal programs work?

Ma-yur (mom canal):

- That is the principle canal that diverts water from glacier-fed streams.

- It’s sometimes constructed alongside contour traces to take care of a mild slope for water move.

- The ma-yur is commonly lined with stones to stop seepage and erosion.

- It might probably stretch for a number of kilometres, bringing water to a number of villages.

Yu-ra (subsidiary canals):

- These are smaller channels that department off from the ma-yur.

- Yu-ra distributes water to particular person fields or clusters of fields.

- They’re designed to observe the pure topography, minimising the necessity for pumping.

- Farmers use easy gates or stones to regulate water move into their fields.

These programs enable locals to adapt to difficult terrains by:

- Utilising gravity for water distribution, lowering the necessity for energy-intensive pumping.

- Maximising using restricted water sources in an arid atmosphere.

- Stopping soil erosion by way of cautious canal placement and development.

- Permitting cultivation on steep hillsides by way of terrace farming.

In the meantime, conventional water storage strategies, like using ponds (rdzing) in Ladakh, could be revived and improved to reinforce water safety in water-scarce areas, notes Dr Chorol.

“Particular person households not often assemble their very own pond. Yearly firstly of spit (spring), ponds are cleared of silts. Villagers collectively undertake the cleansing operation,” notes Dorjey.

However to develop and implement context-appropriate irrigation programs primarily based on these ideas, sure steps need to be taken, argues Dr Chorol:

- Conduct thorough website assessments to know native topography, water sources, and soil situations.

- Have interaction with native communities to include conventional information and practices.

- Design principal canals that observe pure contours and use native supplies for development.

- Implement a community of smaller distribution channels that may be simply managed by farmers.

- Incorporate easy, low-tech water management buildings that may be operated and maintained regionally.

- Promote drought-resistant crops and water-efficient farming strategies appropriate for the native local weather.

- Set up community-based administration programs for equitable water distribution and system upkeep.

“Additionally, integrating customary guidelines and practices, like Ladakh’s sa-ka ceremony earlier than the primary watering of the sector, can improve group buy-in for water conservation efforts. The deep ecological information of native farmers, equivalent to understanding soil moisture (ser) and optimum irrigation timing, could be tapped to enhance irrigation effectivity. Respecting native religious connections, like the idea in water deities (lhu), can promote conservation ethics,” she notes.

“The sa-ka ceremony can improve buy-in for water conservation efforts by reinforcing the cultural and religious significance of water, encouraging respectful use. It additionally encourages intergenerational information switch about conventional water administration, promotes shared accountability for water sources, and creates a way of possession,” she provides.

Lastly, participatory monitoring approaches, impressed by the surveillance position of the chhur-pon and group members in Ladakh’s water distribution system, can guarantee efficient native oversight of water sources. Any efficient water conservation technique in Leh has to begin by first recognising and empowering these native information programs.

“This implies completely documenting and finding out these practices to know their underlying ideas and effectiveness. Then, we have to discover methods to include them into up to date water administration plans and insurance policies. Importantly, we have now to ascertain platforms for knowledge-sharing and co-learning between native communities and exterior consultants, and foster a spirit of collaboration. We should encourage native communities to take care of, revive, and innovate upon their conventional water administration programs,” notes Dr Chorol.

“Most crucially, we have now to make sure that native voices and views are central to the decision-making course of in relation to water useful resource allocation and conservation efforts. The trail to a water-secure future in Leh lies in putting a steadiness between trendy scientific information and the knowledge embedded in conventional ecological information programs,” she provides.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Photographs courtesy Dr Lobzang Chorol, Shutterstock, X/Sahilinfra2, Village Sq.)