“Beti hui hai (It’s a woman).”

Haryana’s Sunil Jaglan recollects how this trio of phrases and the nurse’s accompanying sombre expression modified his life in 2012. Not solely did it swivel Jaglan’s consideration to the problems of feminine foeticide that grips villages in India, but it surely additionally reworked his mindset for the higher.

Admittedly a former patriarch — “In fact, like different boys, I grew up observing my mom and sisters do chores within the house; whereas the boys of the household went to work” — the delivery of a child lady was all it took to remodel Jaglan right into a feminist.

A fast have a look at the 43-year-old changemaker’s life tells me he has a mushy spot for management roles. In his time period as sarpanch (village head) of Bibipur in Jind district from 2010 to 2015, Jaglan set his sights on enhancing the village infrastructure. His ‘Gaav Bane Sheher Se Sundar’ marketing campaign aimed to make Bibipur’s magnificence parallel that of metropolitans.

That wasn’t all. Recalling a landmark initiative throughout his time period as sarpanch, Jaglan reveals off the official panchayat (village council) web site created on the time. The primary of its variety, the web site supplied netizens a complete glimpse of the voters within the village, upgrades in infra, and the village’s historical past. “I was known as the high-tech sarpanch,” he’s pleased with this moniker.

However it was the delivery of his child lady that compelled him to digress from his give attention to village improvement to feminine foeticide. “I by no means imagined this path for my life,” he reminisces, pondering again to his days as a arithmetic coach in his early 20s when working Sundays and the additional cash was all he regarded ahead to.

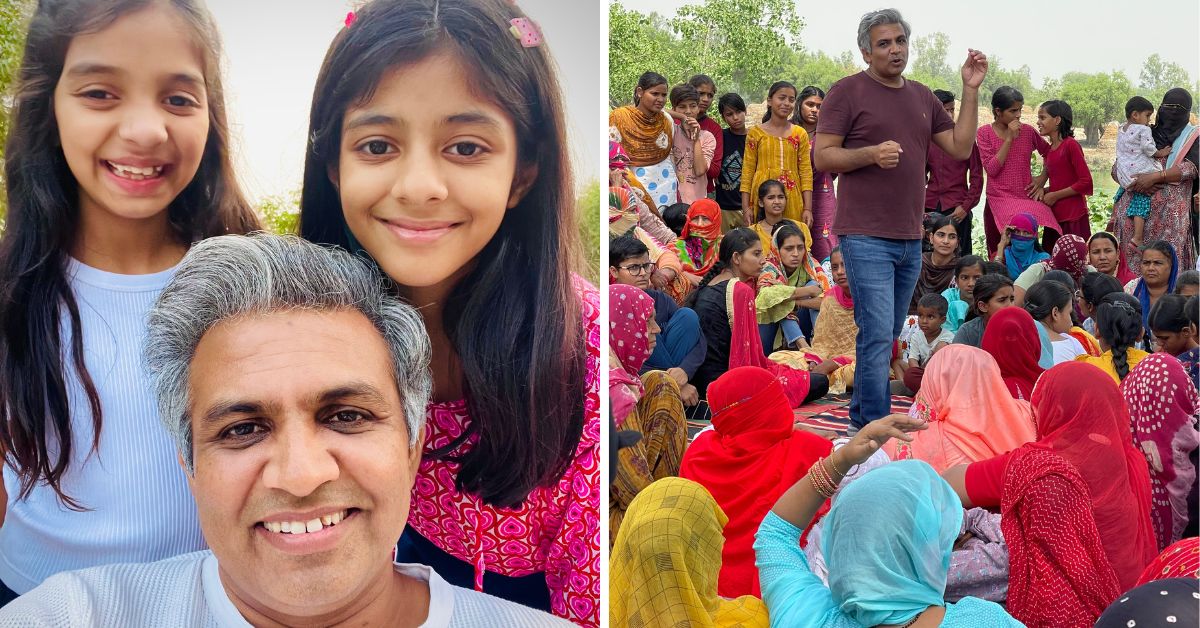

From a youth with easy desires, Jaglan has grown into the proud father of two daughters; instructing India’s technology of males to be higher.

A child lady melts a patriarch’s coronary heart

With each query I pose to Jaglan, I can hear two background voices nudging him when he muddles the main points. It’s a college vacation for Nandini (12) and Yachika (10). Naturally, they’ve picked a spot beside their father for the interview. Having had a front-row seat to his activism work, the duo are well-versed within the particulars.

“Typically, they’ve additionally joined me in their very own scope,” Jaglan mentions.

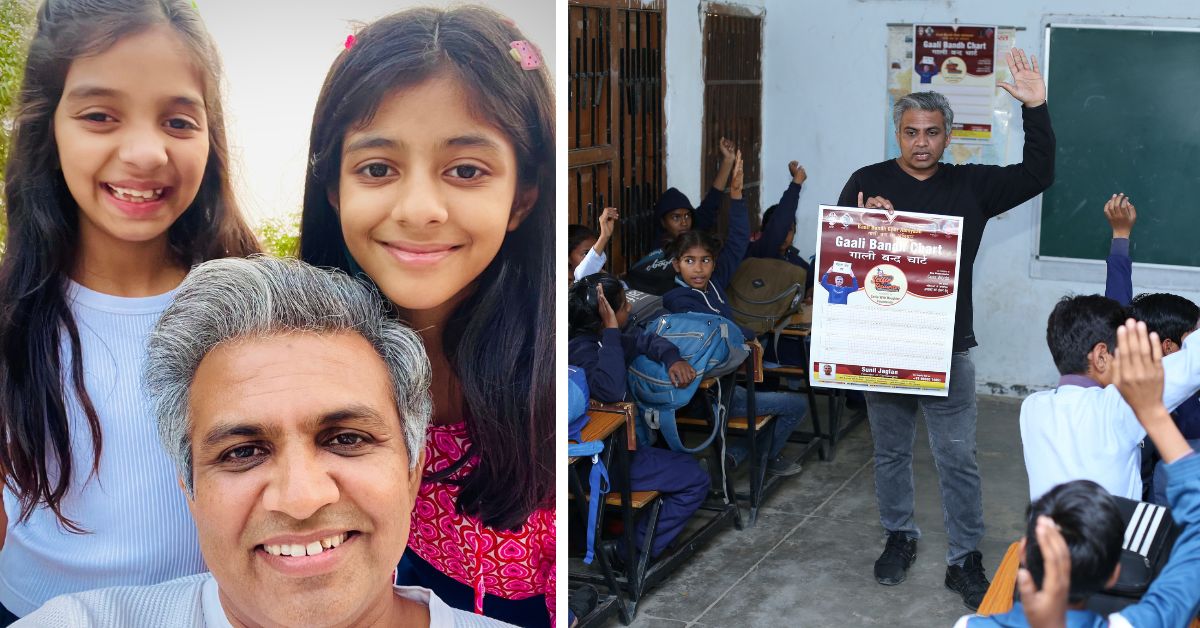

He shares anecdotes of how Nandini would urge her college associates to keep away from utilizing gaalis (Hindi swear phrases) — particularly those who referenced girls — in tandem along with her father’s launch of the ‘Gaali Bandh Ghar’ marketing campaign in 2016.

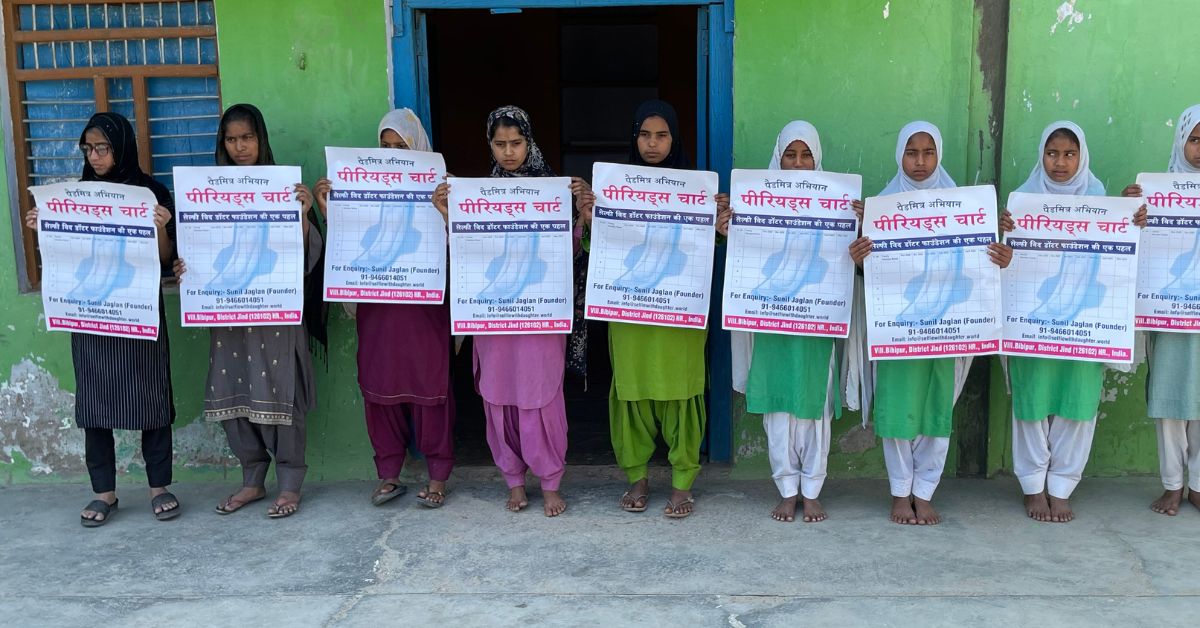

In the meantime, Jaglan’s youthful daughter sellotaped ‘interval rule’ charts within the women’ washroom at her college when she found that a number of women by no means knew what a interval was; tips on how to use a pad; and tips on how to dispose of 1.

So, with the women by his facet, Jaglan tells me the story of the day it began. “Nandini was born in 2012 on Nationwide Woman Baby Day.” Initiated by the Authorities in 2008, the day was earmarked for spreading consciousness about lady kids and the inequalities they should endure.

The irony.

Jaglan recollects the day as one of many happiest of his life. However the nurse and physician on the hospital begged to vary. “After the nurse delivered the information to me that I had turn into a father, I gave her a token as a thank-you gesture. She declined. She stated, ‘The physician will get indignant. For those who had a boy, we might settle for it’.”

He dismissed this as a one-off incident, refusing to let it spoil his celebratory temper. “However after I began distributing sweets within the village, I realised there was a significant issue. To start with, folks would assume that my distributing sweets meant I had a child boy. So they’d congratulate me on it.” When Jaglan informed them he had turn into a father to a child lady, their responses had been often consolatory. “Koi baat nahi, agli baar ladka hoga (Don’t fear. Subsequent time you’re going to get a son).”

And the way would Jaglan reply to those unwarranted sympathies?

“I went and acquired extra mithai and celebrated for a month,” he smiles. “Then I went to the village well being centre to test on the intercourse ratio.”

It was 832 females per 1,000 males in 2011. Some fact-checking on Haryana’s intercourse ratio by means of the years tells me Jaglan shouldn’t have been shocked on the numbers. The state has been (in)well-known for having one of many worst intercourse ratios in India — an issue compounded by patriarchal mindsets prevalent in North India the place elevating a woman has sacrificial connotations.

However, 2023 statistics level out, that mindsets are seeing a shift — there have been 916 females per 1,000 males.

On the time, nevertheless, Jaglan was horrified. He meant to debate this challenge with girls on the subsequent gram sabha assembly. So, you may solely think about his shock when he found that Bibipur gram sabhas had been a male-dominated scene. “Even when girls needed to cross by the spot the place the assembly was being held, they’d cowl their heads in a ghoonghat (conventional headband),” Jaglan shares. The overall consensus was that ladies had been incapable of creating village-level choices. That energy of autonomy rested with the boys.

Agency in his resolve to vary this chauvinist mentality, Jaglan says he started urging girls to be part of chaupals (village conferences), supported by his spouse, sisters, and mom. “In 2012, we arrange considered one of India’s first girls gram sabhas,” he shares. The ripple impact this had was large, and Jaglan determined to go a step additional.

He hosted a khap panchayat in 2012 in Bibipur. An unofficial assembly of clans throughout villages, khap panchayats are traditionally headed and attended by males. However the one which Jaglan hosted noticed 2,000 girls from throughout India convene to debate the problems that oppressed their feminine counterparts.

A historic win!

Among the many points mentioned had been home violence, dowry (a cost given to the groom by the bride’s household throughout marriage), and stress to abort child lady foetuses.

The consequences of the Bibipur mannequin have trickled into Gurugram. As Ramchander, sarpanch of Makhrola village shares, “This mannequin of village improvement was launched in our village a 12 months in the past. Whereas on paper, girls had an equal participation in panchayat committees, the fact was very totally different. Their husbands could be attending instead of them. However now, girls are usually not solely known as for assemblies, they actively take part within the panchayat.”

‘Dadi chahegi toh poti aayegi’

Conversations with younger brides in Bibipur led Jaglan to find the painful existence they’d. They listed a litany of atrocities starting from repeated pointless ultrasounds — not geared toward making certain the nice well being of the newborn, however as a substitute the intercourse; pressured abortions when the ultrasound revealed a woman foetus; and hunger diets to kill the lady foetus when aborting wasn’t an choice.

These points fashioned the bedrock of Jaglan’s marketing campaign ‘Nigrani Rakhna’. “The formulation was easy — I listed moms in Bibipur who had been pregnant for the second, third or fourth time. The gram panchayat then assigned two girls to every of those moms who would monitor her being pregnant progress to time period. We needed to instil worry in those that had been pressuring the ladies to have intercourse dedication assessments.”

Within the meantime, Jaglan zeroed in on retailers in Jind district claiming to have miraculous methods of conceiving a boy. “We shut down 12 of those and cracked down on unlawful intercourse dedication clinics.”

It wasn’t merely Jaglan’s skilled work that was drawing acclaim. The delivery of his daughter Yachika in 2014 — accompanied by Jaglan’s announcement that his household was now full — drew reward from the village. It became an exemplar. “Many households who’ve daughters stopped pondering that they should preserve attempting until they received a son. The truth is, I do know of many males who had a vasectomy executed as they don’t need extra kids. They’re pleased with their daughters.”

Leaning into the thought of a brand new India

The topic of intervals is taboo within the villages of India. Ladies discuss it in hushed tones, whereas males are evasive, treating the subject as one thing legendary. Pads are wrapped in black paper, and menstruating girls are exiled to dwell in gudlus (thatched huts) the place they’re on the mercy of nature.

Many areas of distant India haven’t come to phrases with intervals but.

Now flip your gaze to Bibipur, which is an outlier. Right here, 1000’s of properties have a calendar bearing huge pink circles, denoting the date on which the lady of the house received her final interval. This is part of the ‘Intervals Chart Marketing campaign’ began in 2020 by Jaglan to not solely get the dialog going round menstruation but additionally to alert dad and mom when their daughters had been displaying irregular cycles.

Supriya Biwal is thrilled as she takes me by means of her personal journey of establishing a chart within the hallroom. Having intently labored with Jaglan for 3 years now, Supriya has had a detailed look on the revolutionary impact of his work. “My brother and father didn’t find out about intervals. However I made charts for my mom, aunty, and myself, and put them up on the wall.”

“Log jhijhakte the (Folks had been hesitant to speak about this stuff),” she says. “However now my brother and father discuss intervals comfortably.”

Jaglan and his staff didn’t cease at charts. “We spoke to the dad and mom and daughters about vaginal an infection, sanitary pads, weight loss program, and vitamin. We additionally began conversations with males about menopause. Lots of them considered it as a time when the interval cycle stopped. However they didn’t find out about its emotional implications.”

Supriya’s private favorite was the ‘Daughter’s Nameplate’ marketing campaign. It advocated for the daughter’s names to be listed on the house porch. “I discovered it attention-grabbing as a result of often, the nameplates have the names of the dada (paternal grandfather) or father.” Supriya proudly states that the nameplate of her house boasts her identify. “I didn’t cease at my house. I made an analogous nameplate for a lot of different girls too,” she shares.

Ticking his different campaigns off a psychological guidelines, Jaglan sheds gentle on the ‘Lado Pustakalaya’ initiative by means of which libraries had been created in 5 villages of Haryana; the ‘Beti Padhao Abhiyan’ which coaxed women’ dad and mom to let their daughters full their schooling as a substitute of marrying them off early; and naturally, probably the most viral ‘Selfie With Daughter’ (2015) marketing campaign, which obtained point out from Prime Minister Narendra Modi in addition to former president Pranab Mukherjee.

Celebrities and iconic personalities jumped onto the bandwagon importing a selfie with their daughter in tune with the marketing campaign’s messaging of giving particular recognition to lady kids to permit them to develop to turn into empowered human beings.

Moreover, Jaglan popularised the idea of the ‘Lado Panchayats’, urging girls to take a stand for his or her points. “The village chaupals started seeing plenty of girls. I might encourage illiterate girls to go up on stage and discuss their issues; this was revolutionary.”

Witnessing the scope and scale of his work, the Authorities leaned into his mannequin and Jaglan recollects working with former president Pranab Mukherjee. “I grew to become a senior advisor on the Pranab Mukherjee Basis. My position was to duplicate the Bibipur mannequin of village improvement throughout India.”

If you’re studying this story, Jaglan has requested me to convey one thing:

He doesn’t need so that you can assume he was born with a superhero cape. “I used to be and am odd. It’s the ache of the ladies in my life that reworked me. My aim is that in the future when the squeals of a child lady are heard in rural India, the one response must be smiles,” he remarks.

Edited by Pranita Bhat