New analysis into the bizarre methods snow distorts sound presents new hints in regards to the extraordinary looking methods of a winter phantom—the Nice Grey Owl.

From the Winter 2024 subject of Dwelling Chook journal. Subscribe now.

Maybe no species of owl is as fantastically tailored for looking in snow because the Nice Grey.

Discovered all through the boreal forests of the Northern Hemisphere, Nice Grey Owls dine totally on small mouselike rodents referred to as voles. In winter, voles retreat to tunnels deep underneath the snow—however that doesn’t cease Nice Grays. Looking from an uncovered perch, an owl listens intently for its goal, then swoops down from above, punching by way of the crust of snow with its lengthy, highly effective legs. In a position to attain prey nearly 18 inches beneath the floor of the snow, Nice Grey Owls have been recognized to penetrate snow crusts thick sufficient to help a 175-pound individual.

What hasn’t been clear, regardless of a long time of analysis about Nice Grey Owls, is how they do it—how do Nice Grays hunt prey animals not than a ballpoint pen, which they will’t see, utilizing solely faint burrowing sounds greater than a foot underneath the snow to information them in plunging strikes with surgical precision?

Some intriguing new hints arrived lately through quirky analysis carried out by an unlikely pair of scientists. One, a California biologist who had spent most of his profession finding out the sounds made by hummingbird feathers, had lengthy dreamed of working with owls; the opposite, a Canadian professional on owl discipline biology, had at all times wished to check sound.

Of their examine, the researchers explored how Nice Grey Owls use a set of finely tuned diversifications for gathering sound and localizing its supply in deep snow. The Nice Grey Owl’s facial disc, a bowl-shaped circle of feathers that frames its face, is the biggest of any owl species, gathering and directing even the softest sounds from the surroundings towards its ears. And like different owls that hunt by sound, its ears, hidden underneath feathers, are asymmetrical. A better ear opening on one aspect than the opposite enhances its potential to pinpoint a sound’s exact location.

To check the hunting-by-hearing capabilities of Nice Grays, the researchers used an array of microphones buried underneath the snow to hold out a posh and distinctive set of experiments within the chilly of Manitoba. Their analysis, printed within the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in November 2022, uncovered new hints in regards to the bizarre methods snow muffles and distorts sound—and the Nice Grey Owl’s unbelievable potential to listen to a vole hidden within the snow, which it seems relies upon largely on the owl’s distinctive feathers.

Two Unlikely Specialists Staff Up

“I’m a hummingbird biologist. I do know this a lot about working with owls,” admits Chris Clark, holding up his thumb and pointer finger with a tiny hole between them.

Clark, a biology professor on the College of California, Riverside, started his profession finding out the mechanical sounds hummingbirds make with their feathers throughout show flights. About 14 years in the past, he grew to become fascinated with the other idea—how some birds (particularly owls) decrease the noise they’d in any other case naturally produce in flight. He initially struggled to get any owl discipline analysis off the bottom, however in 2021, he was contacted by a nature documentary crew making a movie about animal sounds. And, the filmmakers talked about, they had been additionally working with a Nice Grey Owl professional in Manitoba.

That professional was Jim Duncan. Duncan has been finding out Nice Grays for nearly 4 a long time, and after he retired because the director of Manitoba’s fish and wildlife company in 2018, he began his personal nonprofit group, Uncover Owls, targeted on analysis, outreach, and conservation. Duncan recollects when, as a PhD scholar on the College of Manitoba, he carried out his first analysis on Nice Grey Owls and spent the night time in a snow hut referred to as a quinzhee. On a bitterly chilly February night time on the Taiga Organic Station in jap Manitoba, Duncan realized how snow muffled outdoors sounds.

“You don’t hear any individual strolling as much as your quinzhee till they’re proper outdoors,” he says. “So it simply grew to become this nagging query in my thoughts: What sounds are these owls listening to, and the way are they utilizing them to catch meals?”

The main target of his PhD dissertation was elsewhere, and he lacked the coaching and tools essential to pursue that query, so he set the query apart— till, over 30 years later, the documentary crew launched him to an professional on chicken flight and sound in California.

Quickly, Clark paid for a airplane ticket out of his personal pocket, packed each piece of heat clothes he owned alongside together with his acoustic evaluation tools, and headed for Manitoba. On the floor, the objectives of their collaboration had been easy: to check how snow would possibly take up and deform the sounds of voles and the way that may have an effect on Nice Grey Owl looking methods.

“Owl Ears” vs. “Mouse Ears”

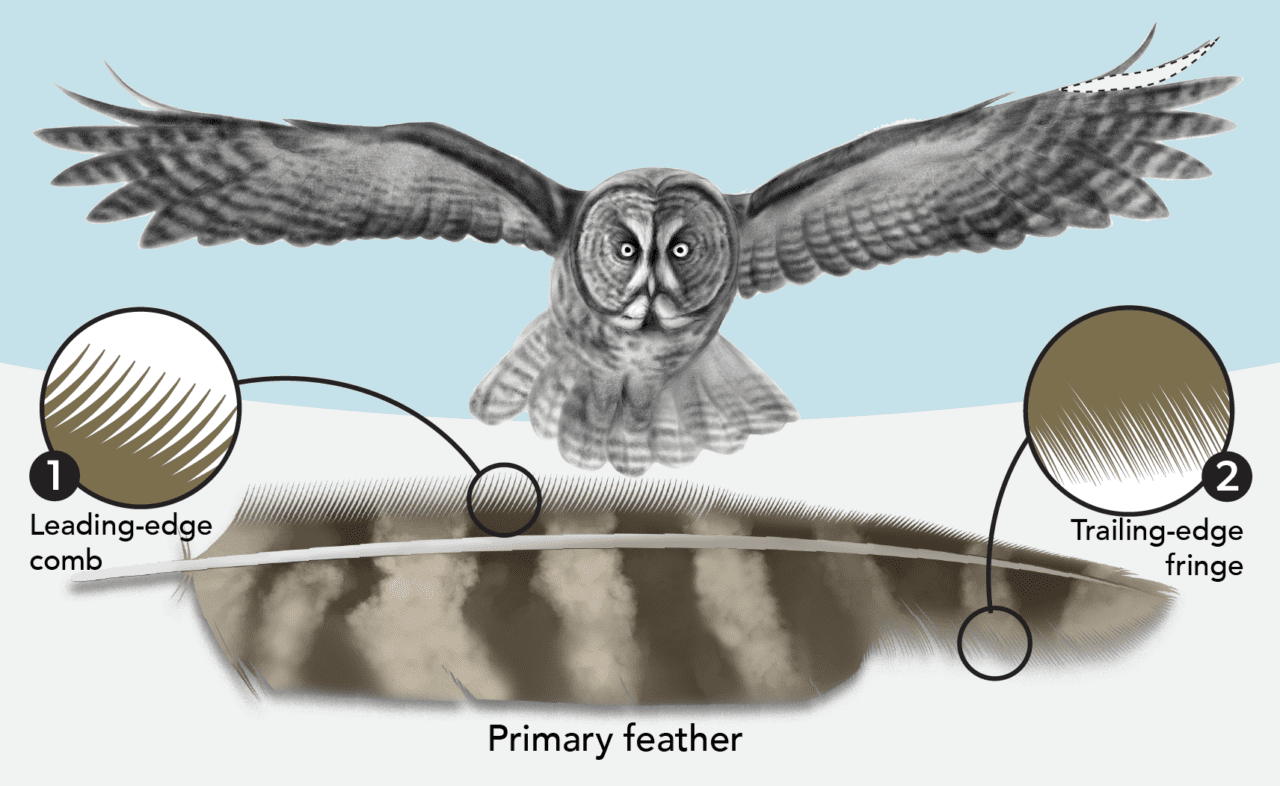

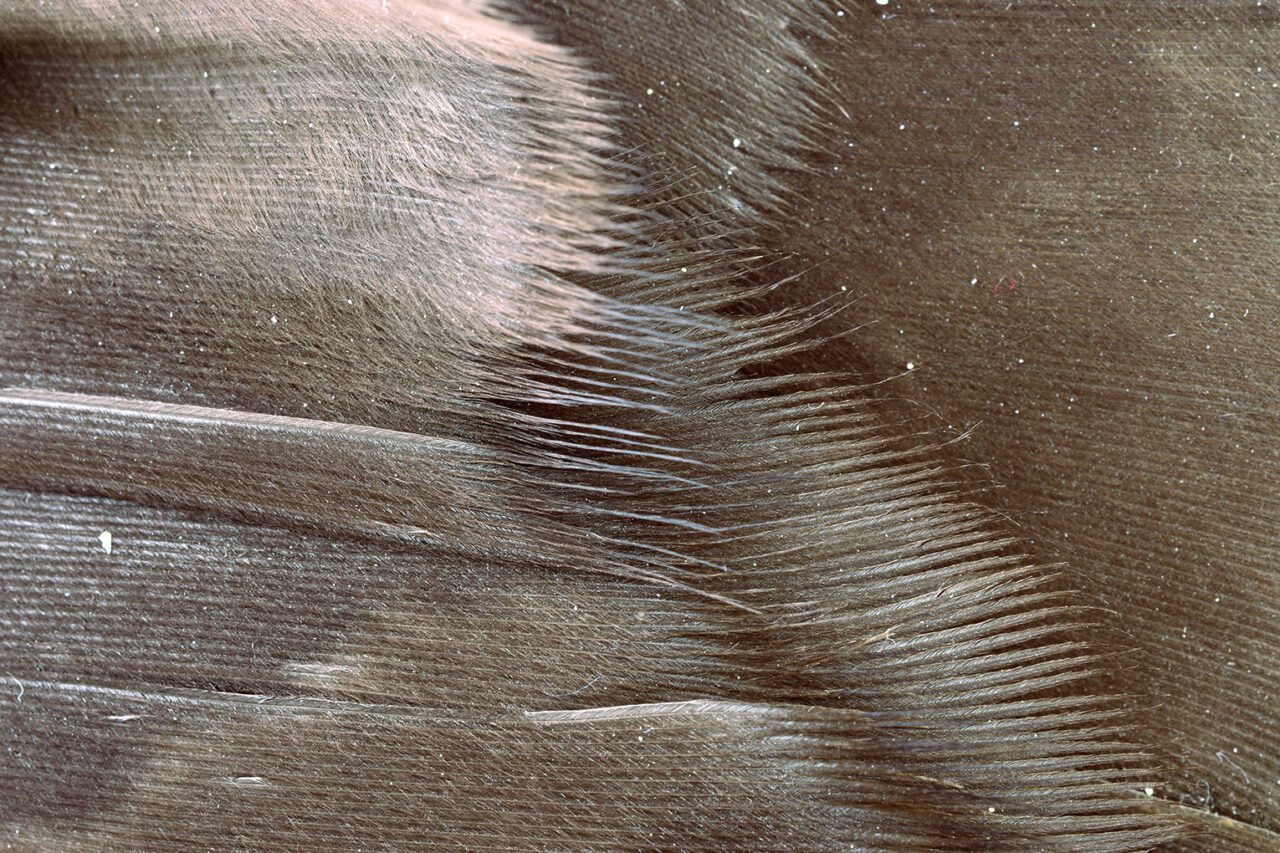

Nice Grays use stealthy flight to shock their unsuspecting prey. Owls normally are recognized for flying nearly silently, however intriguingly, Nice Grays take these traits to the intense. Of all owl species on the planet, Nice Grays have the longest comblike serrations on the main edges of their wings, and the thickest velvety coating on their flight feathers—each evolutionary diversifications for silent flight that scale back wing noise to nearly nothing.

There are, says Clark, two major hypotheses to clarify why owls advanced to fly quietly: “What I name the owl-ear speculation and the mouse-ear speculation.” The owl-ear speculation is that owls fly quietly to keep away from interfering with their very own potential to detect prey by sound; the mouse-ear speculation is that they’re making an attempt to keep away from being detected by potential prey.

“Though these hypotheses aren’t mutually unique,” explains Clark, “there are some instances the place they make totally different predictions, and the number-one case is when the surroundings itself blocks sound,” akin to when there’s a thick layer of snow on the bottom. The owl-ear speculation suggests {that a} snow-hunting owl ought to have particularly well-developed quieting options, in order that it might probably hear its muffled prey over the sound of its personal wings. Underneath the mouse-ear speculation, nevertheless, quieting options can be much less vital, as a result of the snow would offer the owl with pure stealth.

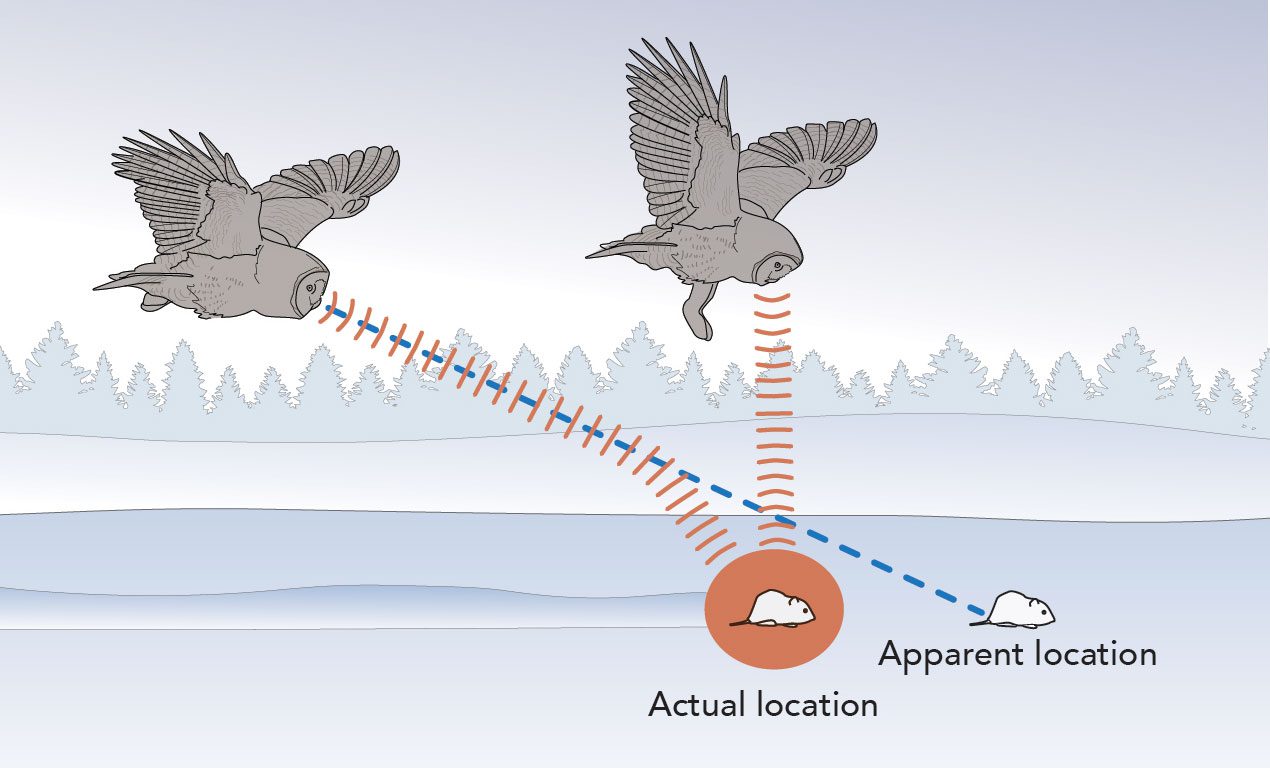

However snow does extra to sound than merely dampen it. A snowpack is surprisingly advanced, half ice and half air, with totally different densities at totally different depths—all affecting the transmission of sound. High and low sounds go by way of snow in several methods, and due to the totally different speeds at which sound travels by way of air and ice, snow would possibly even refract sound, bending it in order that it appears to return from a distinct location than its precise supply.

Heading to a web site 60 miles northeast of Winnipeg, the place Duncan knew owls hunted, he and Clark positioned contemporary plunge holes from Nice Grays pursuing voles. They dug into the snowpack and slipped a water-proof speaker beneath, taking part in white noise or recordings of voles digging. Then, they pointed an acoustic digicam that Clark lugged from his UC–Riverside lab on the snow. An acoustic digicam makes use of an array of 40 microphones to localize the place a sound seems to be coming from, then superimposes this obvious supply location on a digicam picture.

Working with digital tools in temperatures as little as –16°F introduced some difficulties: “I’ve solely skilled chilly temperatures like that a few instances earlier than in my life,” says Clark, the Californian. Each the laptop computer he used to run the acoustic digicam and the audio system taking part in the sounds repeatedly froze up and stopped working, limiting the variety of trials they had been capable of do. Finally, Clark and Duncan had been solely capable of full six profitable trials with the buried speaker.

However even these six trials had been sufficient to offer some intriguing new insights into the challenges a Nice Grey Owl faces when looking in winter—and the way it overcomes these challenges.

Refraction, Attenuation, and Acoustic Mirage

The outcomes from the acoustic digicam supplied detailed knowledge about how snow impacts sound in two methods: refraction and attenuation.

On this case, attenuation is the time period for the way in which a blanket of snow muffles sounds. Clark and Duncan’s outcomes confirmed that low-frequency sound is way much less affected than high-frequency sound, making Nice Grey Owls’ monumental facial discs—particularly well-suited for gathering low-frequency sound—an excellent adaptation for looking in deep snow. However the acoustic digicam additionally confirmed the second, weirder manner snow impacts sound. Sound is certainly bent because it travels by way of the snowpack, shifting its obvious supply by as a lot as 5 levels relative to the precise place of the buried speaker— a phenomenon that Clark and Duncan dubbed an “acoustic mirage.”

This impact is minimized once you hear from immediately above the sound’s true supply, which helps clarify a particular facet of Nice Grey Owl looking conduct: hovering. Simply earlier than an owl plunges into the snow, it usually hovers in midair for a couple of moments, frenetically beating its wings. This tactic probably offers an owl an opportunity to lock in on a vole’s precise place from the purpose the place the acoustic mirage is minimized. Some fish-eating birds—akin to ospreys, kingfishers, and gannets—choose to strike straight down at their underwater prey for comparable causes, though they’re coping with water bending gentle as a substitute of bending sound.

Clark sees two potential ways in which these snow sound results may play into Nice Grey Owl excessive diversifications for quiet flight. On the one hand, maybe the owls’ quieting options on their wing feathers particularly suppress low-frequency sound, making certain that sound from an owl’s personal wings doesn’t intrude with its potential to listen to the low-frequency digging sounds of the voles. Or, maybe (and that is the state of affairs he thinks is extra probably) they might be particularly suppressing sound throughout hovering, in order to not intrude with an owl’s potential to focus on its prey precisely throughout this important last second.

“Once they’re hovering, you’ll be able to see the feathers behind the wing lifting up. That’s a sign that a part of the wing is stalling, which is when the air stops flowing easily over the floor of the wing and begins to kind quite a lot of turbulence,” says Clark. Turbulence creates sound, which these wing options may have advanced to counteract. Different birds that hover whereas looking, akin to kestrels and harriers, have velvety wing coatings like owls.

Each of those prospects are per the owl-ear speculation, not the mouse-ear speculation. Neither rationalization for the owl’s quieting diversifications is about serving to the owl sneak up on voles, which may’t hear the owl coming regardless, buried as they’re underneath a sound-attenuating blanket of snow. As an alternative, in response to Clark and Duncan, these diversifications make sure that Nice Grays can hear voles over the sound of their very own wingbeats as they lock onto their unseen prey’s place.

Katherine Gura, a researcher on the Teton Raptor Middle in Wyoming and professional on Nice Grey Owl ecology, who was not concerned with this acoustics examine, was “thrilled” when she learn Clark and Duncan’s paper.

“This work serves as a superb instance of the fascinating questions we are able to reply by merging a robust data of the bodily properties of snow with wildlife ecology,” she says. “By testing how sound travels by way of the snowscape and linking these findings to Nice Grey Owl foraging methods and morphology, this examine begins to unravel how this species advanced its distinctive winter conduct and traits.”

Gura says that Clark and Duncan’s analysis is a vital first step for additional research on whether or not these snow-hunting acoustic diversifications of the Nice Grey Owl can maintain up over time, because the Earth continues to heat—and snowy winters soften away.

“This work opens the door for higher understanding how altering snow regimes doubtlessly will have an effect on Nice Grey Owls and different species that depend on subnivean [under the snow] prey,” says Gura. “Their potential to forage—and finally persist—in a altering world stays unknown.”