From the Summer time 2023 subject of Residing Chook journal. Subscribe now.

The Could household has a wildfire security plan in place for his or her 15,000-acre natural-range ranch simply north of the Arkansas River, on the southeastern plains of Colorado.

So when 60-mph winds whipped a wall of flames throughout the bone-dry ranchland in April of 2022, everybody knew the protocols meant human security first. Circle the bulldozers and earth-moving equipment across the ranch home to chop firebreaks. Hold a transparent path to the freeway for household pickup vehicles. Name within the ranch palms.

Think about the livestock subsequent. With greater than 9,000 acres of the ranch on hearth and smoke blanketing the air, the Mays, their ranch palms, and some good neighbors knocked down fences to supply escape routes for his or her 800 head of Limousin cattle.

On that fateful day when his land went ablaze, ranch patriarch Dallas Could had different animals on his thoughts, too—all the opposite creatures nice and small that he’d spent years cultivating on his shortgrass prairie, which was designed to be a wildlife sanctuary. By spring 2022, Could Ranch had change into a famend refuge for Black Rails and Lesser Prairie-Chickens, extraordinarily uncommon black-footed ferrets and Northern Pintail geese, elk, and Golden Eagles.

Because the wildfire smoke cleared the following day, and Dallas Could noticed how the blaze had scorched even the richest wetlands, he despaired for what the 100-degree summer season days would convey to the blackened prairie.

For years, the Could household—Dallas alongside along with his mom, brother, and sister, in addition to his spouse Brenda and their three kids and 6 grandchildren—had invested in a distinct sort of cattle ranching. They teamed up with Geese Limitless, Audubon, the Denver Botanic Gardens, The Nature Conservancy, and federal and state wildlife companies to push the sprawling ranch towards a way forward for sustainable agriculture on restored native habitat. As Could remembers pondering, the partnerships and enthusiasm for making his ranch a sustainable operation had moved his mindset from feeling prefer it was “us in opposition to the world” to “discovering all of the organizations and individuals who worth the wildlife habitat right here.”

Now the fireplace had turned most of his ranch into drifting sand resembling “the Sahara Desert,” Could mentioned, a couple of days after the fireplace. “It’s going to be an actual take a look at of our program. Whether or not the grass regenerates itself and we get again, or if we’re not sustainable.”

Earlier than the Fireplace, a Wildlife Renaissance

Six years earlier, in Could of 2016, Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientist Andrew Farnsworth was searching for birding spots alongside the Decrease Arkansas River Valley when he occurred on Could Ranch.

Farnsworth, a Cornell Lab senior analysis affiliate on the BirdCast undertaking, was scouting for Workforce Sapsucker. That yr, the group’s Large Day birding run—an annual one-day blitz to listing a number of species and lift a number of cash for hen conservation—was set in Colorado. And the shortgrass prairie grasses waving within the breeze simply past the Could household’s fenceposts promised a bonanza of hard-to-find grassland hen species that will be nice will get for his or her Large Day depend.

“There have been only a complete lot of birds,” Farnsworth mentioned. “We might see the pristine facet of the ranch, and the facet managed for extra biodiversity, and it was simply an eye-opener. We thought, ‘This might be an amazing spot.’”

Farnsworth arrange a recognizing scope on a dust highway, close to a creek and dryland pasture, and scanned for Nice Blue Herons and Burrowing Owls—whereas holding out hope for sounds that will verify native reviews of the elusive Black Rail. That’s when a pickup truck got here angrily barreling down the highway. Dallas Could, an imposing rancher with the carriage of John Wayne, thought the recognizing scopes had been gun sights, and his cattle operation has little persistence for poachers.

Excessive feelings on either side shortly reworked right into a fortunate birding tour. The abruptly cheerful, ruddy-faced Could begged the birder to comply with his pickup truck to his fastidiously tended wildlife ponds. Promising Large Day plans had been again on.

When Farnsworth stepped out of the automobile at a Could Ranch pond on Large Sandy Creek, he virtually instantly heard the piercing chitter of the Black Rail. Could and his household heard Black Rails on a regular basis, however didn’t know the way coveted they had been by birders. The noisy however shy Black Rail—a species generally heard however not often seen—wasn’t even on Workforce Sapsucker’s want listing for Colorado.

“There’s no means,” as Farnsworth put the preliminary chance of getting a Black Rail on their Large Day roll name. Because it turned out, his probability encounter with an initially prickly rancher was dozens of birds that Workforce Sapsucker placed on their listing from the Could Ranch on their record-setting birding run. Workforce complete: 232 species, the state document for hen species listed in 24 hours in Colorado.

Dallas Could wasn’t stunned in regards to the birds to be discovered on his ranch. On the time, his household had been more and more working their working lands as a wildlife haven for 4 years. With pond restorations, meticulous grazing rotation, and a live-and-let-live perspective towards prairie canine, the Could household and their ranch palms had gotten accustomed to seeing Lesser Prairie-Chickens strutting by way of a pasture, Burrowing Owls taking up prairie canine dens, and Lengthy-billed Curlews wading for crayfish.

After many years shepherding their household’s cattle ranch by way of good instances and unhealthy, the Mays had a brand new plan for his or her drought-challenged, multi-generational ranch within the river valley: rewilding the pasture areas the place his livestock grazed, and making a living off greater than elevating a herd of beef.

The brand new mannequin of sustainable grazing that Could dove into requires piecing collectively all of the accessible proof that their environmentally progressive ranch produces added worth. It’s an rising means of ranching and farming, one which acknowledges preservation of habitat amid international local weather change can convey revenue and survival.

As Could places it, they run a biology lab as a lot as they run a ranch.

“It’s a distinct philosophy,” he mentioned in late 2021, standing at his equipment store close to cages holding 15 federally endangered black-footed ferrets resulting from be launched by way of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service program. The Could Ranch is getting funds from nonprofit teams to host a post-reintroduction monitoring program. And the ferrets would eat the prairie canine, making room for the Burrowing Owls that nest in prairie canine holes, and in flip including to the advertising and marketing attraction of beef that comes from an Audubon-certified, bird-friendly ranch.

“We function our ranch in a completely pure means,” Could mentioned. “We do our greatest. We’re an island of grass in a sea of developed farmland.”

A Ranch Restored for Prairie, Grass-Fed Cattle, and Carbon

The transformation of the Mays’ ranching and farming property—which begins a couple of miles north of the city of Lamar and is reduce by Large Sandy Creek because it drains towards the Arkansas River—started in earnest in about 2012. That’s when the Mays, who had leased property for grazing their high-quality Limousin beef for many years, purchased the place.

Ranching and farming is a tight-margin enterprise to start with, however add in a giant mortgage (somewhat than inherited land) and it turns into almost not possible. The Could household wanted most earnings off their land to make a go of it. Elevating grass-fed beef—as a substitute of sending cattle to an industrial-sized feedlot to fatten up on corn—would increase the highest line by fetching a premium from patrons. Conservation measures that lowered prices—like switching from flood irrigation to drip irrigation for rising alfalfa and hay for feed—would improve the cash that made it to the ranch’s backside line. It didn’t harm that the Could household is elevating a water-conscious number of livestock in Limousin, that are traditionally tailored to dryland grazing and an ideal cattle breed for shortgrass prairie.

However by Could’s calculations the ranch nonetheless wanted extra money on the highest line, with household plans for the following generations—three Could kids and their rising brood of grandchildren—to take over sometime. So the Mays acquired inventive with stretching their advertising and marketing and revenue sources to the property’s fences.

In 2015, the Could household signed a conservation easement, a contract by which a conservation group pays the rancher or landowner for giving up growth rights and agreeing to maintain the land as open house. Because it turned out, the Could Ranch adjoins an influence substation and is blasted by the identical sizzling solar and prairie gusts that energy windmill farms and photo voltaic arrays throughout southeastern Colorado. Since they closed on the ranch buy, the Mays had already fielded dozens of provides to lease the land for photo voltaic or wind energy that might be cheaply plugged into the grid by way of the substation. However The Conservation Fund, a nationwide land conservation group devoted to defending environmentally invaluable land, was prepared to pay to make it possible for by no means occurred by buying a conservation easement on the ranch.

Subsequent up, Dallas Could invited biologists from the Audubon Rocky Mountains workplace to the household ranch. After Audubon Rockies Government Director Alison Holloran made the drive from Fort Collins, she stepped out onto the shortgrass prairie, noticed the in depth wetland habitat, and was astonished.

“Oh my goodness,” Holloran remembers telling Could, “I promise you, you’ve acquired extra secretive marsh birds on this ranch than anyone can think about.”

The ranch was shortly added to the Audubon Conservation Ranching Initiative, which offers a certification as a bird-friendly place to lift beef. (The Could Ranch was later designated as an Audubon State Necessary Chook Space.) Now the Mays can get a little bit further bump on the worth of their grass-fed cattle, and their beef might be featured on the menus of upscale eating places in Denver’s burgeoning River North neighborhood.

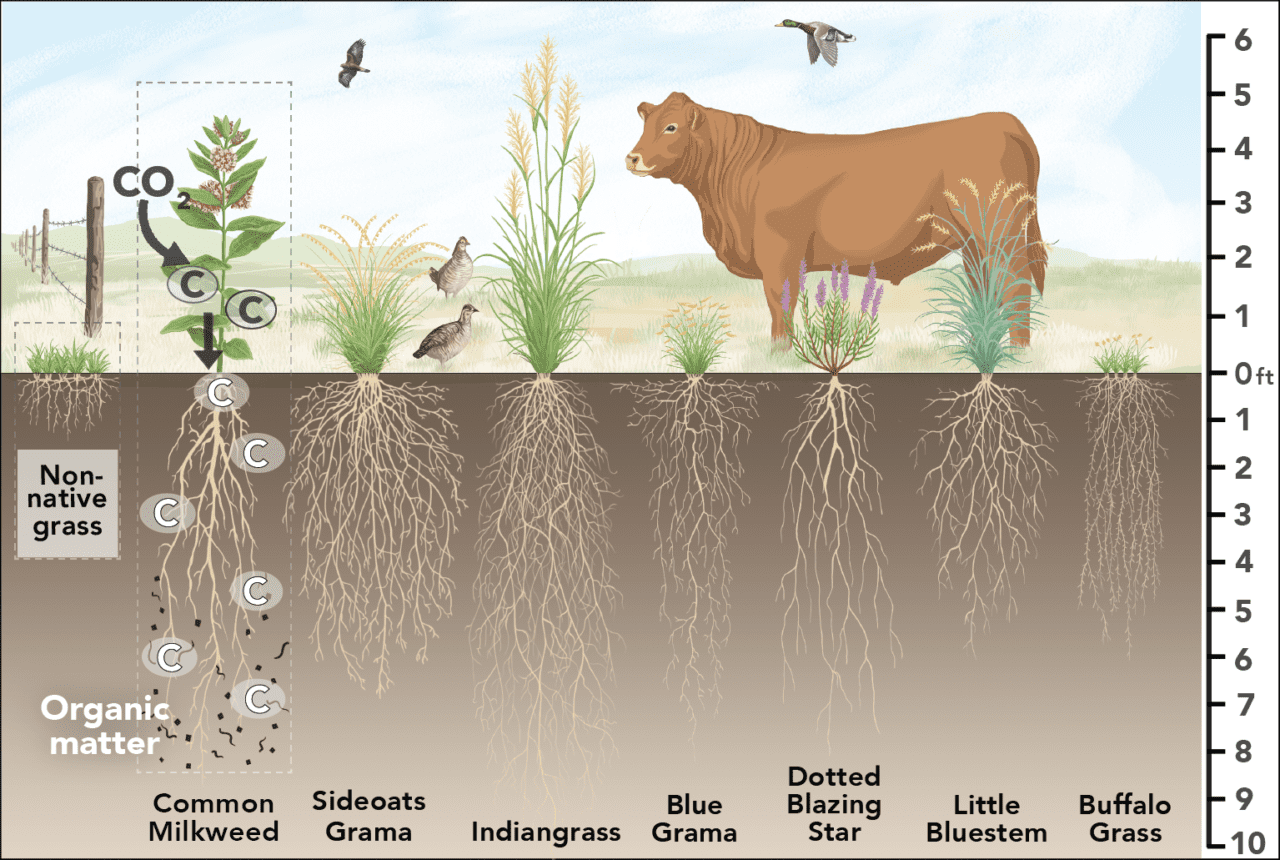

To spherical out the cattle-ranching conservation trifecta, the Mays offered a contract on the worth of what their prairie grazing pastures had been nurturing underground. Buffalo grass, which alongside grama grass dominate shortgrass prairies, can run its roots so far as 6 ft underground, burying carbon all alongside the way in which.

Geese Limitless, a conservation group historically related to preserving wetlands for waterfowl, was prepared to facilitate the drafting and sale of a carbon-credits contract for the Could Ranch property by way of the DU Carbon Program. This system hyperlinks up open-space property homeowners with companies and donors who will purchase carbon credit for grassland preservation. A 2014 sale of carbon credit to Chevrolet to offset fossil gas impacts was a giant launch for this system, touted as a game-changer by the Obama administration’s Division of Agriculture.

As for what Geese Limitless will get out of the deal, Billy Gascoigne—a grassland carbon retention and sequestration specialist and DU director of agriculture and strategic partnerships—says conserving the shortgrass prairie on the bottom, as a substitute of churned up for row crops, is vital for preserving populations of pintails, wigeons, and teal on the western plains.

“What many individuals don’t notice is that waterfowl are grassland-nesting birds,” Gascoigne mentioned.

The Could Ranch, Gascoigne mentioned, “is the final steady piece of native prairie that also reaches the Arkansas River.” In different phrases, the 15,000 acres of shortgrass prairie are a carbon-sequestration gold mine that, with safety, will keep away from the discharge of greater than 200,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions over the lifetime of the undertaking, in keeping with a DU analysis.

The carbon-credits income to the Could Ranch reaches 5 figures yearly, so “not an enormous windfall,” Gascoigne mentioned. “However it may be a gradual revenue stream that didn’t exist 5 years in the past.”

“We weren’t speaking about carbon sequestration 10 years in the past, however we’re speaking about it now,” mentioned Paul Evangelista, a Colorado State College analysis scientist in pure assets ecology and knowledgeable on trendy pure ranching. “Not solely as a result of there’s a potential financial acquire from it, nevertheless it’s an vital piece in sustaining all the ecosystem. So we’ve this actually fantastic shift within the pondering of some ranchers.”

Increasingly more agriculture leaders are desirous about working with researchers and conservation teams to exhibit how land conservation and elevating business animals can cohabitate, Evangelista mentioned.

“I do truly suppose ranching could also be extra of an answer to the issue than most of the people has made it out to be,” Evangelista mentioned.

Awards and Rewards

In Could 2021, the Could Ranch was chosen for a Colorado Leopold Conservation Award, named after the Sand County Almanac writer and naturalist Aldo Leopold. The award acknowledges farmers and ranchers “who encourage others with their voluntary conservation efforts on personal working lands.” The Could Ranch was chosen for achievements in bettering wildlife habitat, soil circumstances, water high quality, and for restoring the general ecological group. For instance, the awards committee identified the outcomes of a Denver Botanic Gardens plant survey on the Could Ranch, which discovered greater than 90 native plant species not beforehand documented in Powers County.

Awards apart, the Could Ranch is starting to understand a number of the rewards that may help this sustainable ranching mannequin. Whereas many western ranchers battle predatory coyotes regularly, the Mays imagine leaving prairie canine alone and offering hen habitat provides coyotes lots to eat in addition to younger calves. The Could Ranch has by no means shot, trapped, poisoned, or in any other case killed a coyote, Could mentioned, except it was inadvertently hit by a automobile late at night time.

“And in 45 years, as tens of hundreds of calves have been born on this ranch, I can truthfully say we’ve by no means misplaced a calf to predation,” he mentioned.

Years of expertise in grazing rotation and grass restoration have given the Mays a head begin in assembly any new federal necessities that will include the current U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designation of Lesser Prairie-Chickens as a threatened species in Colorado below the Endangered Species Act. Not too long ago relocated members of one other federally protected species, black-footed ferrets, spent their first winter on the ranch from 2021 into 2022. And the circle of ranch life was renewed within the spring with the primary births of calves. As of April final yr, the Mays had been optimistic about their ecological and monetary future.

“We’re taking part in the lengthy recreation,” Dallas mentioned. “The brief recreation can be to go in and run as many cattle as we might and switch the assets into money move. That’s not sustainable. That’s not the sort of factor that’s going to maintain you on the panorama.”

One new actuality that the Could household has accepted alongside the way in which is the fixed scrutiny of certification auditors. Farmers have at all times complained they’ve self-appointed companions within the type of bankers. Now eco-friendly ranchers have groups of investigators poking across the ranch—the water-quality of us, the birds and biodiversity screens, the easement assessors, the carbon sheriff.

Looking for the sanction of outsiders is now a essential a part of environmental ranching, mentioned Dustin Downey, the supervisor of the conservation ranching program for Audubon Rockies. Downey is a cattle rancher himself, along with his personal herd grazing on grasslands within reach of Satan’s Tower. He mentioned that if donors and customers are going to place their cash into beef labeled as bird-friendly, they need to know that the certifications and awards are primarily based on statement and science.

“We need to maintain ourselves to the very best commonplace attainable relating to Audubon for our conservation-minded membership,” Downey mentioned.

The Could household spent many years and numerous hours within the saddle or behind a tractor wheel, restoring grazing lands to shortgrass prairie and managing the land for kids and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, on into perpetuity. However on that gusty, dry April day in 2022, Dallas Could feared that the sturdy conservation-ranching framework his household’s future trusted was going up in smoke.

How Quick Can Burned Land Heal?

A mere 4 months after the fast-moving wildfire burned up almost three-quarters of the Could Ranch and turned it right into a desert of blowing sand, the grass was again.

By the primary day of August final yr, thick, emerald-green grass stretched from the creek to the horizon on the spot the place County Highway LL dives below Large Sandy Creek, a desk of inexperienced felt pinned down by blackened willow stumps.

Dragonflies crowded the airspace over the creek, executing lateral dashes in the hunt for an in-flight meal. A wholesome bloom of algae floated below plenty of contemporary bulrushes, a significant accent coloration to the recovering beaver ponds.

Dallas Could took within the sights and sounds of therapeutic land and unfold his broad shoulders as broad as his grin.

“It’s all again,” he beamed.

Two fortunate weeks of monsoon rains in July had pumped life again into Could Ranch. The downpours had Dallas Could mopping water off his kitchen ground resulting from roof harm, however he wasn’t sad about it—as a result of the large plans for the way forward for the prolonged Could household had been again on.

“It’s been a great summer season,” Dallas mentioned, buying and selling observations creekside along with his son Riley.

“What the ranch desperately wanted was rain,” he mentioned, which appeared implausible provided that the Rocky Mountain West continues to be within the grips of a 22-year historic megadrought. However, “we’ve gotten rain once we wanted it.”

Perhaps it’s karmic payback for all the great vibes that the Could household had put into their land since they purchased it.

Their purebred Limousin cattle had been out on the pasture grazing a thriving alfalfa crop—consuming into their winter foodstock, however nonetheless a welcome scene. The Black Rails and different birds that helped Could Ranch earn its Audubon beef certification had been nesting and breeding in recovering wetlands. The carbon-storage contracts the ranch offered have been adjusted to acknowledge all of the carbon launched by the wildfire, however these losses ought to be offset in the long term by rain-restored root development that stuffs extra carbon underground.

The Mays nonetheless fear in regards to the parts of the ranch that have a tendency towards the sandhill ecology. Drought had thinned out the grass cowl in these areas, and the fireplace burned into roots in a means that may delay a comeback.

However in different areas, they see the payoff of their lengthy recreation. Deeply rooted grasses like sacaton have come again shortly, giving cattle one thing to eat whereas different grasses with shorter roots take their time.

“The restoration course of has vindicated our administration, and the significance of biodiversity, having a mess of species on the market,” Dallas mentioned. “All of them react in numerous methods to these traumatic occasions.”

Having walked his cattle pastures for almost half a century, Dallas Could is practiced on the lengthy recreation. The Limousin now grazing his property are descended from a heifer born in 1971 that was given to him by his grandfather. Wanting throughout his pastures that tilt south towards the Arkansas River, Could was pondering again even additional to 1871, and earlier than—earlier than fences, earlier than settlers using burgeoning railroad programs worn out most wildlife—to a time when bison walked the identical land. Their hooves broke the onerous soil and planted seeds; their grazing and defecating unfold and fertilized grasses.

At its core, Dallas mentioned, the Could Ranch is a working mannequin that proves landowners may help convey again that unique prairie ecology—the prairie birds, the waterfowl, the burrowing animals, the deer, the raptors, and the ungulates, each wild and home.

“If the cattle are grazing the proper means,” he mentioned, “they’re a profit to the surroundings.”

Andrew Farnsworth, the Cornell Lab Large Day scout who stumbled into Dallas and his hen haven on the prairie, says the Could Ranch operates on a timeless precept for a way farmers and ranchers can take into consideration wildlife and habitat.

“My land is vital,” Farnsworth mentioned in describing the Could household ethic. “I need to use it in ways in which I can survive, but in addition do the proper factor.”

In regards to the Creator

Michael Sales space is a reporter who covers the surroundings for the Colorado Solar, a journalist-owned, award-winning information outlet primarily based in Denver.